Bergoglio Crucifies Jesus All Over Again

"Who is Jorge Mario Bergoglio?"

"I am a sinner. This is the about authentic definition. It is not a figure of spoken communication, a literary genre. I am a sinner."

Cordoba, Argentina

The room is small and red.

Heavy scarlet defunction, red-tiled flooring, ruby-red coverlet on the bed. A painting of the Crucifixion is the just adornment.

Information technology looks similar a cell: a monk'southward or a prisoner'southward.

This is Room No. 5 of the Jesuit residence in Cordoba, Argentina.

Outside this solitary space, on the other side of its thick stone walls, students flock and scatter like birds. Buskers try their hand at American dejection. Street vendors militarist bootleg pipes.

Just in Room No. 5, all you hear is the insistent echo of your own thoughts, your lonely prayers to a faraway God.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the human who would become Pope Francis, spent two years in this room during the 1990s.

Information technology was a night night for a homo now known for his megawatt presence and huge flock of followers. He was 50 years old, forsaken by many fellow Jesuits, left to suffer in silence. It was, he would afterwards say, "a time of great interior crisis."

This is the story of why Jorge Mario Bergoglio was exiled to this room -- and how the painful lessons he learned here are transforming the Cosmic Church.

Finding Francis in Cordoba Video past Rich Brooks, CNN

Cordoba lay in darkness when I arrived tardily on a July nighttime, save for the dim halo of high streetlamps. My misconceptions about the city became clear by morning.

Cars honked through rush hr. Stylish shops and fancy restaurants crowded the narrow streets. Dodging downtown traffic, I thought: This is where the Pope was exiled?

Information technology may be 500 miles from Buenos Aires, only Cordoba is no Elba Island. More 1.iii million people telephone call the city home. Information technology's bigger than Dallas and twice the size of Boston.

By risk, my showtime day in Cordoba was July 31, the feast solar day of St. Ignatius, who founded the Jesuits. It was a good day to officially begin my mission here.

Virtually every aspect of Pope Francis' life, from his career as a bouncer to his critiques of capitalism, has been picked apart by the printing and a troop of talented biographers.

But every bit he prepares to make his maiden voyage to the Usa, his time in Cordoba -- a dramatic passage for i of world's most famous men -- remains shrouded in mystery. In many timelines of the Pope'south life, the years 1990-1992 are an empty, unexplained gap.

THE PEOPLE'S POPE

CNN's Chris Cuomo explores how a humble scholar became a religious stone star. Encounter the people and places that shaped Pope Francis in a CNN special report, "The People's Pope," Tuesday at 9 p.one thousand. ET.

I plowed through biographies, read dozens of manufactures and combed through every interview I could discover, looking for references to his time in Cordoba. I even wrote the Holy Father a letter. A long shot, I know. More a prayer than a petition.

Receiving no reply, I tried another tack. I came to the city of his exile. Hither in Cordoba, I planned to walk where he walked, kneel where he prayed, see the people he met and read the words he wrote.

Since the early days of his papacy, I've suspected that one of Francis' cardinal letters -- that even the worst sinner is deserving of mercy -- is more than a sentiment from the Catholic catechism. It has the ring of real experience.

And so I found myself in Cordoba'due south cultural heart, the Manzana Jesuitica -- the Jesuit Cake -- a 17th-century complex that includes a alpine stone church, a pocket-size chapel and the cloistral residence where x Jesuits live.

I thought it'd be proficient luck to attend Mass on St. Ignatius' feast day. Students from the nearby colleges packed into every pew of the Iglesia de la Compania, the Jesuits' church building. Stuck in the back row, I couldn't hear most of the local bishop's homily, simply I did grab the words "Papa Francisco" several times.

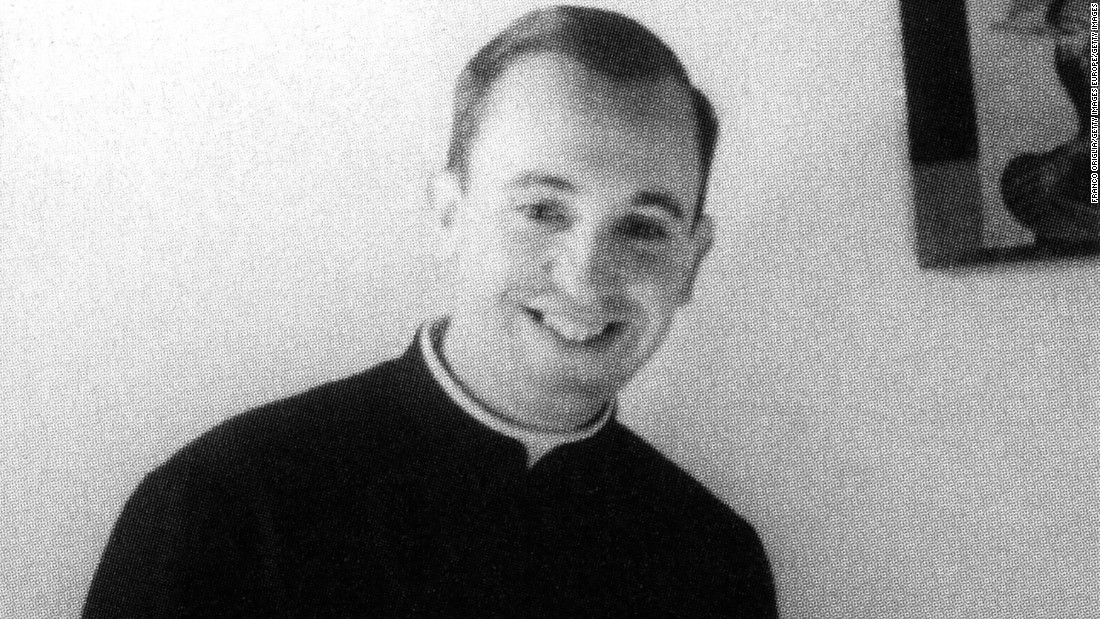

Some 57 years ago, the future pope came to Cordoba as a fresh-faced Jesuit novice, his pilus and cassock coal-black. He was 21, most the same age as the students sitting beside me at Mass.

In a picture from 1958, the year Bergoglio entered the Society of Jesus, he looks confident and happy. His mother, who had wanted her eldest son to study medicine, appears humble.

The futurity pope with his parents, Regina Sivori Bergoglio and Mario Jose Bergoglio, in 1958.

Bergoglio'due south call to priesthood was mysterious but potent, interrupting an otherwise ordinary adolescence. Information technology was a spring twenty-four hours in Buenos Aires when he passed a church and was lured similar a fish to a line.

The 16-yr-old entered a dark berth where a priest was hearing the sacrament of penance.

"Something strange happened to me in that Confession," he later said. "I don't know what it was, but it changed my life."

It was Bergoglio's offset stupor from the "God of surprises," a deity who lies in wait and springs upon souls unawares.

He would after learn that God's surprises cut both ways.

The day after Mass, I went in search of Jesuits who recollect Bergoglio from his days in this city.

The building where he began his Jesuit career has been bulldozed, replaced by a supermarket. But a keeper of its memories, the Rev. Andres Swinnen, lives just across the street, at Parroquia de la Sagrada Familia, a Catholic parish.

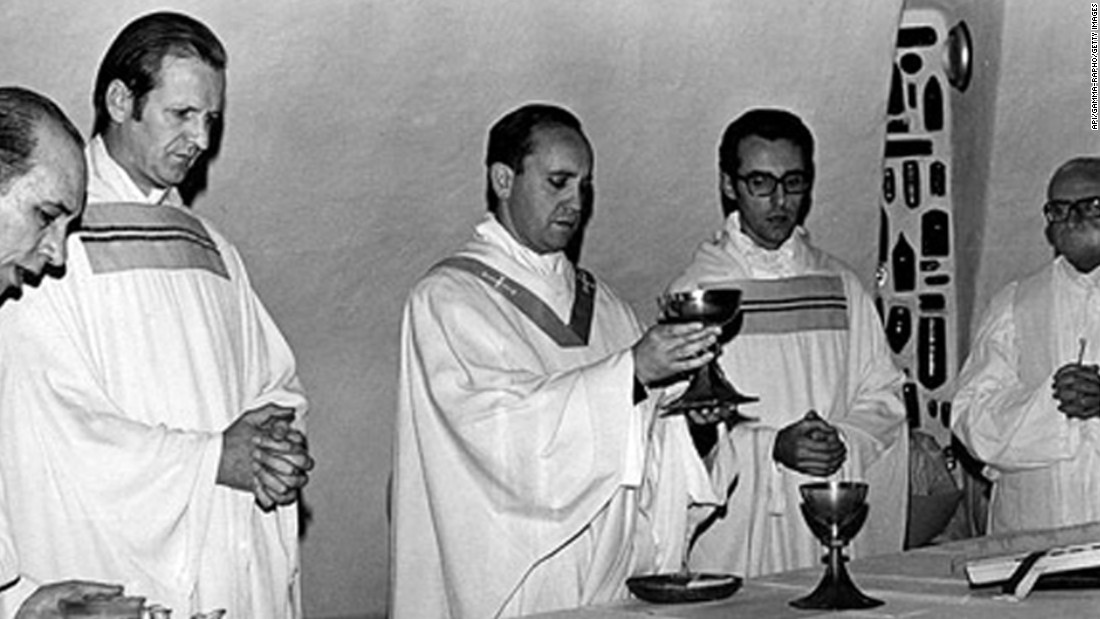

Andres Swinnen, 2nd from left, and Bergoglio, center, in 1976. The 2 friends entered the Jesuits a year apart.

Swinnen entered the Jesuits one year earlier his friend Bergoglio, and is at present in his 7th decade with the Guild of Jesus. He is tall and elegant, with swept-dorsum silver hair and an aloof air of nonchalance. As he opened the door of his parish, I motioned across the street to the site of the sometime novice house.

"You haven't moved very far," I teased, earning myself an center-coil.

Similar Bergoglio, Swinnen said he joined the Jesuits because he admired their tight communities, missionary focus and disciplined lives. The novices' fourth dimension was managed downwardly to the minute. "The schedule was set up. The habits were set. You had to study at a certain fourth dimension."

The austerity extended beyond the structured schedule. They used soap as toothpaste and paper every bit toilet newspaper, Swinnen recalled. Only last names were allowed, to ward off over-familiarity.

"It sounds like the military," I said.

Swinnen shrugged.

It takes more than than a decade for Jesuits to consummate their training, which includes theological and philosophical studies, hands-on ministry building and intense spiritual retreats. The thought is to railroad train a company of men able to go anywhere and fulfill any mission, all for the "greater glory of God."

Bergoglio hoped to travel to the Far Eastward, similar his Jesuit heroes. But his asking was denied because of a lung ailment that nearly took his life.

Instead, Bergoglio's mission field would be closer to home.

Outside the room where Pope Francis stayed in Cordoba for ii years.

Efifty Museo de la Memoria sits just a few blocks from the Manzana Jesuitica in Cordoba. It's a former police station where dozens of Argentines -- suspected guerillas or mere impediments to the military machine's brutal rule -- were tortured and killed.

Equally many as 30,000 Argentines were slain or "disappeared" from 1976 to 1983, a period known as the Dirty War.

The walls of the memory museum are lined with pictures of victims, some taken in their last moments, as they are dragged into the police station, and some showing happier days before they were arrested.

Walking through the museum, seeing the artifacts of interrupted lives, you realize why the Muddy State of war remains an open up wound on Argentina'southward soul. Just earlier the go out, in lieu of a proposition box, a sign pleads for data most los desaparecidos, the disappeared. As I walk out, a woman sits on the steps, crying.

Bergoglio was appointed provincial of the Argentine Jesuits when he was just 36. (The Guild of Jesus divides itself into geographic regions called provinces, which are led by provincials who serve six-year terms.)

It was 1973, iii years before the military insurrection and the beginning of the Dirty War. Bergoglio had finished his germination simply two years earlier.

His maturity impressed Jesuit leaders, merely his rapid rising was also aided past a series of misfortunes.

The man more likely to take been named provincial died in a car crash, at a time when the Jesuits' ranks were already thinned by convulsive changes in the Catholic Church.

The Second Vatican Council, convened in Rome in 1962, was supposed to throw open the church building'due south windows and let in fresh air. Religious orders were encouraged to re-examine their original "charisms" or distinct gifts and missions.

Some Jesuits took this as a license to experiment with their vows of chastity, poverty and obedience. Past the time Bergoglio was appointed provincial, a generation of Jesuits had slipped through Vatican II'southward open windows. The province was in disarray.

As head of the Argentine Jesuits, Bergoglio faced pressures from inside and exterior the church.

Bergoglio moved quickly to establish society. Besides quickly, some Jesuits grumbled.

Simply the church pressures paled in comparison to the political atmosphere.

Jesuit residences were repeatedly raided by the ruling military junta. Swinnen said soldiers greeted him at gunpoint. The message was clear: The Society of Jesus was beingness watched.

In function, this was because Jesuits across Latin America were trading their breviaries for broadsheets. Liberation theology -- the idea that the Gospels express a "preferential option for the poor" -- was taking hold. Not content to serve in the slums, Jesuits were asking why and so many Latin Americans were so poor in the first identify. Detractors called them "communists in cassocks."

Bergoglio's colleagues say he kept a low profile, neither publicly praising nor condemning the military. His task was to protect the priests under his care.

Two Jesuits made that very difficult.

Under the influence of liberation theology, Franz Jalics and Orlando Yorio organized a "base community" in a Buenos Aires barrio, where they urged the poor to face their oppressors.

Bergoglio allowed the priests to teach the Catholic faith but warned them to be wary of the military machine. They would be safer living with the balance of the Jesuits, he said.

Jalics and Yorio refused.

Eventually, Bergoglio gave Yorio and Jalics an ultimatum: Cull the barrio or the Society of Jesus. They chose the barrio.

Several days afterwards, armed men seized the two Jesuits.

Bergoglio says he pursued every avenue to salve them. After five months, the junta relented and released the Jesuits.

For years, Yorio blamed Bergoglio for the kidnapping, accusing the provincial of leaving him unprotected and fingering him to the military.

Jalics was more reticent, maxim only that he and his onetime provincial had reconciled. (Afterward Pope Francis' election, Jalics said that he did non arraign Bergoglio for his capture.)

Because of the intensity and lingering pain of the Dirty War, I expected the Jesuits' kidnapping to be the principal source of tension during Bergoglio's time as provincial. Had this led to his exile to Cordoba?

But even Jesuits who didn't like Bergoglio don't blame him for what happened to Yorio and Jalics. They had other bug with him.

Borrowing from the Jesuit "ranches," Bergoglio taught his students nigh farming and animal husbandry.

When I heard nearly the "Jesuit ranches" near Cordoba, I pictured a priest wearing a cowboy hat, a stalk of straw between his teeth.

Sadly, these ranches, which one time bankrolled the Jesuits' missions, are now museums, with nary a moo-cow in sight.

Bergoglio resurrected aspects of the ranches, though, incorporating the unlikely academic subjects of farming and animal husbandry when he became rector of the Jesuit seminary in Buenos Aires.

The Rev. Alfonso Gomez recalls those days with a bemused grinning, as if he notwithstanding can't quite believe his own retentivity.

A studious and serene man, Gomez is the terminal person you'd look to tell a pig-wrestling story. But presently after welcoming me into his spacious office at the Catholic University of Cordoba, Gomez relates, with relish, the tale of The Sow That Almost Escaped.

"Information technology was fun," Gomez said with a wide smile. "It was difficult, too, but many of us liked information technology. It was a very well-organized organisation."

It was Bergoglio'due south platonic consignment: forming young Jesuits.

After serving in high-powered posts like provincial, many Jesuits are "demoted" to discourage careerism and appetite, a sin that Ignatius chosen the "female parent of all evils."

The Society of Jesus symbol is seen on Jesuit buildings around Cordoba, including this one at a "ranch."

Merely Swinnen succeeded Bergoglio as provincial and made his friend rector of the Colegio Maximo, a decision that would divide the province for decades.

Bergoglio's fashion of germination, like the strict system he mastered in Cordoba, was minutely managed. He insisted on punctuality. Stragglers were sent to clean the kitchen.

"If you lot broke any of the rules there was ever some kind of social or moral sanction," said the Rev. Rafael Velasco, who studied at the Colegio Maximo.

"There was very little time for freedom. Information technology was more like a convent than a Jesuit business firm."

Bergoglio discouraged his students from reading liberation theology and reassigned professors who taught it, alienating politically minded Jesuits.

He preferred more direct ways of helping the poor, building farms effectually the seminary, making young Jesuits milk the cows and harvest the crops. The nutrient fed the surrounding barrios of Buenos Aires.

Seminarians would become straight from classroom to the pigsty, a pungent reminder of the Jesuits' aspiration to "find God in all things."

But many of the more than intellectual Jesuits preferred classrooms to cows. They wanted more intellectual freedom and fewer chores. A rupture inside the province began to emerge.

Even Jesuits outside Argentina -- especially those committed to liberation theology -- were bemused past Bergoglio'south methods.

Just Bergoglio was a stiff personality, Jesuits said. Once he fabricated a decision, he could rarely be swayed to reconsider.

Even more troublesome for the province, his devotees honored Bergoglio'southward every discussion equally holy writ. And, after property high Jesuit office for fifteen years, he had attracted a sizable entourage, possibly 40% of the province.

The Rev. Arthur Liebscher, an American Jesuit studying in Argentina during the 1980s, remembers Bergoglio's retinue equally brash and cocksure.

"Prophets are fine," he said with a laugh, "but their disciples are really hard to have."

Bergoglio'south followers were certain that their leader had carved out the 1 true path. Other Jesuits weren't so certain.

Bergoglio would occasionally say Mass at the Iglesia de la Compania, the church inside the Jesuit Block.

Inorthward 1986, Bergoglio'southward half dozen-year term as seminary rector concluded. Liberation theologians, whom he had removed from positions of power, now ran the province, appointed past Jesuit leaders in Rome.

One of their beginning tasks was to decide what to practise with Bergoglio.

They sent him to Deutschland to finish his doctoral thesis, perhaps hoping that his absence would heal hostilities inside the province. It might also get his mind off Jesuit formation.

Simply Bergoglio was 50 years old, with decades of pastoral experience, now stuck in dusty stacks of German libraries. At night, he took walks near the airport, waving at planes leap for Buenos Aires. He was restless and homesick.

After just 3 months in Frg, Bergoglio decided to get dwelling, a small act of rebellion against his Jesuit superiors. They allowed him to return and to teach a class at the seminary in Buenos Aires. He looked like a different man, some Jesuits say. His hair was shaggy; his fingernails long.

But Bergoglio's presence presently reignited the onetime debates over how to exist a proper Jesuit.

Bergoglio, for the about part, tried to stay removed, leading past example instead of argument. But the debate took on aspects of Latin American politics, Jesuits say, with the campaign revolving around the "caudillo" -- the potent man. His coterie clashed with the new Jesuit superiors, and Bergoglio did little to stop it.

"My impression is that he was aware of the great goals he had," said Liebscher, "merely he didn't realize that, in the process, he was stepping on a lot of honorable people."

Finally, Bergoglio's bosses decided they'd had enough. They shipped him off to Cordoba, 500 miles away.

Brother Louis Rausch remembers calling Bergoglio presently later he heard the news. It was 1990.

"Have you packed your suitcase?" he asked.

Rausch is toothpick-sparse, with wavy hair, hipster glasses and an excited style of speaking. As a Jesuit brother, he is a fellow member of the Society of Jesus but not an ordained priest.

When I asked Rausch how well he knew the future pope, he pulled a letter of the alphabet from his pocket. In it, Bergoglio teased him virtually his countrified family. It was Rausch who taught farming at the Jesuit seminary.

Now Rausch runs the Iglesia de la Compania, the Jesuit church building. He recalled that his friend didn't reply the question near packing for Cordoba. Just Rausch understood what the silence meant.

"He knew that the time alee would be very hard."

Earlier they hung up, Bergoglio asked his friend: Are you praying for me?

Ricardo Spinassi was the housekeeper at the Jesuit Residencia when his old friend Bergoglio lived there.

When he arrived at Room No. 5 in Cordoba, Bergoglio was a priest without a portfolio. At least, not 1 that would occupy much of his heed or time.

His official duty was to hear confessions, listening in his room for the buzz of the doorbell to tell him that some guilt-wracked soul wanted to unburden itself of sin.

Some confessors, though, avoided the priest with the solemn face. There were whispers that he was unwell.

Occasionally, Bergoglio would say Mass, filling in for the head priest of the Iglesia de la Compania. He tried to finish his doctoral thesis, merely, as with many long-procrastinated projects, inspiration'south burn had dimmed. He set it bated, unfinished.

Instead, he read and prayed, thought and wrote, musing about his childhood days, about the problems that plague religious communities. He plowed through a five-volume history of the popes.

When he needed a modify of scene, Bergoglio walked to the Iglesia de Cristo Obrero, a lone effigy in black following the path of the Primero River equally information technology softly streamed within high stone walls.

When I visited the church, the graffiti slogans outside outnumbered the parishioners inside. It was ornate and sepulchral, with piffling natural lite filtering in from the bright day exterior. A few sometime women prayed in the pews, passing rosary beads through wrinkled hands.

I wanted to know more about what Bergoglio did in Cordoba, how he filled his long days, and then I visited Ricardo Spinassi, who was the housekeeper at the Residencia for 33 years.

Spinassi said his old friend was a creature of habit.

He began each day with the same chore, washing one of his 2 pairs of socks, and ate the same meal -- vegetables and chicken -- for tiffin every day.

In the early morning time hours, he prayed in the Jesuits' domestic chapel, alone with the bones of Jesuit saints.

The domestic chapel where Bergoglio prayed lone every morning.

"He was there even earlier the old church ladies," one Jesuit said with a smile.

In the afternoon, while other brothers took postal service-lunch siestas, Bergoglio bowed his caput for several minutes before a statue of St. Joseph, a favorite Christian figure since babyhood.

"He prayed similar a saint," Spinassi said.

Bergoglio frequently helped with housework, preparing meals, folding the laundry and changing the soiled sheets of sick and elderly Jesuits.

Spinassi said that Bergoglio also offered more significant assistance, giving him nine,000 pesos donated by High german nuns to purchase his house.

Bergoglio gave Spinassi grief, though, when he visited the house and found a pool in the backyard. Spinassi said there had been a mistake: He had only asked for an higher up-ground pool. But Bergoglio boiled.

"He was very angry at me," Spinassi said with a hangdog look. "And he was right."

Spinassi permit me see the puddle, but only if I promised not to take pictures. He didn't want the Pope to encounter them and become angry once again.

He believes that Francis doesn't live in the Churchly Palace, the traditional papal residence, considering Pope John Paul II installed a pool.

(At that place is no pool at the Apostolic Palace, simply at that place is ane at the papal summer residence, Castel Gandolfo. Francis has refused to live in either palace.)

The bones of Jesuit saints have a place of laurels on the domestic chapel's altar.

I asked Spinassi what Bergoglio did for fun during his days at the Jesuit Residencia. He looked at me silently for several moments.

Did he watch TV?

No, not actually. Except for the occasional soccer match.

Did he drink cocktails or play cards?

No. When he received whiskey for his birthday, he gave it abroad.

Did he chat with the other Jesuits?

No. He kept to himself, Spinassi said.

Bergoglio did receive a few visitors, young man Jesuits worried about his health.

"You would hear that he was not doing well," said Liebscher, the American Jesuit. "There was a real concern there."

Bergoglio grew gaunt and spent many hours in solitude.

"He understood that he had to remain silent and obedient because he was being punished," said Rausch.

"Some people said he was crazy," said Velasco, ane of the Jesuits who studied nether Bergoglio in Buenos Aires. "But that was non true."

Velasco said he visited Bergoglio in 1990, not long after the exile began. They talked about the Society of Jesus, and Bergoglio tried non to be critical, simply couldn't help himself.

He fumed at being pushed aside like an one-time piece of furniture and accused Argentina'south Jesuit leaders of uprooting the club from its traditional missions.

But he saw no way out of exile.

"If you don't agree with the superiors who the Society accept assigned you," Velasco said, "then you lot have a problem with the entire Gild."

It is normal for Jesuits, fifty-fifty talented leaders, to move from loftier to depression assignments. Merely some said that casting Bergoglio out to Cordoba was clearly a punishment, and that he was suffering.

"I saw it in his face," said the Rev. Juan Carlos Scannone, an elderly Jesuit who has known Bergoglio since the 1950s. "I could run into he was going through a spiritual purification, a night night."

Cordoba is Argentina's second-largest city, but for Bergoglio information technology was a lonely exile.

Why did Bergoglio take his time in Cordoba so hard?

His Jesuit colleagues had different explanations.

Some said that he was humiliated to have been tossed aside and given such an unimportant job. Or that he had lost his purpose in life. Others said he saw his vision for the Society of Jesus slipping away. And that he securely missed the bustle of Buenos Aires.

I of the men who sent Bergoglio to Cordoba, the No. 2 Jesuit in Argentina at the time, emphatically denies that it was a punishment.

"The reasons for allocating a Jesuit from one house to another, and from one activity to some other," said the Rev. Ignacio Garcia-Mata, "found the ordinary mode of the society since it was founded by St. Ignatius."

None of Bergoglio's friends told me they actually spoke to him about Cordoba. It'southward every bit if the subject was as well emotional or embarrassing.

Simply I did find 2 journalists who managed the scoop of all scoops: an interview with the Pope himself.

Their book, "Understanding Pope Francis: Key Moments in the Formation of Jorge Bergoglio equally a Jesuit," has just been published in English.

A devout Cosmic, announcer Javier Camara has pictures of Francis throughout his house, including i of him and his married woman meeting the pontiff last twelvemonth.

Camara invited me and his co-writer, Sebastian Pfaffen, to his home for a traditional Argentine asado. Over ruby-red wine and steak (salad for this vegan) we talked well-nigh the Pope's time in Cordoba.

In Cordoba, Bergoglio ofttimes prayed at this shrine to Jesuit founder St. Ignatius.

Even the city'due south ardent Catholics don't know Bergoglio spent time here in the 1990s, the journalists told me. He wasn't a large bargain at the fourth dimension and didn't socialize much.

Instead, the Pope told them information technology was a "time of purification."

"It is a dark time, when one does non see much. I prayed a lot, I read, I wrote quite a bit and lived my life," he said. "What I did in Cordoba had more to do with my inner life."

The Pope didn't divulge much about his interior darkness, but Camara and Pfaffen located documents that offer insight into Bergoglio's mind, if non his soul.

Bergoglio worked on several essays during his fourth dimension in Cordoba. One is chosen "Silencio y Palabra" -- "Silence and Give-and-take."

Information technology was written, he said, to help religious communities overcome serious disagreements. From the first judgement, the essay strikes a personal tone.

"When we discover ourselves in a hard situation, sometimes silence is non an act of virtue," Bergoglio writes. "Information technology is simply imposed upon us without any choice."

Merely fifty-fifty imposed silence can exist a grace, he continues.

Drawing on the "Spiritual Exercises," the set of prayers and contemplations he learned decades before as a Jesuit novice, he explores the divergence betwixt self-pity and self-cede.

"It could happen that one falls into a kind of spiritual victimization," Bergoglio writes, "considering that 'they hurt me without any reason.'"

While his brothers took siestas, Bergoglio bowed his head at a statue of St. Joseph.

The simply way to avoid such thinking, he concludes, is to stay humble, keep praying and give God the room to work.

But what happens when God seems absent-minded from the scene?

That's the theme of some other essay Bergoglio published when he was in Cordoba, "El Exilio de Toda Carne," "The Exile of All Flesh." The essay began as notes for a spiritual retreat Bergoglio led in 1990, several months before he began his own exile, lending the text a shadow of premonition.

"The human or woman who consciously takes charge of his exile suffers a double loneliness," Bergoglio writes.

They are lonely amidst the crowd, strangers in a strange country. But they also taste a spiritual loneliness, "the bitterness of solitude earlier God."

This isolation is felt nigh acutely in prayer, Bergoglio writes, when the exile sets himself apart from others -- in the tranquillity of a dark chapel, perhaps, before his brother Jesuits have awoken.

The exile too feels this isolation in prayer itself, when he contemplates the distance between his desires and God's plans.

The Hebrew prophets felt this pain, Bergoglio writes, citing Jeremiah, who told God he was also immature to deport such weighty responsibility.

Still, Jeremiah carried out his mission, trying to lead the Hebrews through political turmoil. In the end, he was remembered only for the "infighting" and contradictions he left backside, Bergoglio writes.

Jeremiah's mission failed, leaving the exile anguished, weeping by the rivers of Babylon. Some scholars suggest that he lapsed into a period of silence. Unsure of how to get back home, the prophet reached for his last resort: prayer.

"It's the prayer of a man who gave everything, and would like -- at least -- that God would exist on his side," Bergoglio writes. "But in life, sometimes it seems as though God puts himself on the other side."

The Rev. Angel Rossi says Cordoba changed Bergoglio for the ameliorate.

Nearly anybody I spoke to in Cordoba encouraged me to interview the Rev. Affections Rossi, a man Pope Francis refers to as his "spiritual son."

On my terminal day in the metropolis, I managed to sit down with him in the domestic chapel of the Manzana Jesuitica.

Rossi looks a bit like a young Bergoglio: same wire-frame glasses, same salt-and-pepper pilus.

In spiritual matters, they could be twins. Rossi leads the Jesuit community at the Manzana Jesuitica, as well equally running a charity, delivering lectures, directing spiritual retreats and writing.

Bergoglio accustomed Rossi into the Social club of Jesus in 1976, when the onetime was provincial. By Rossi's interpretation, they lived under the same roof for seven or eight years.

I asked him to describe Bergoglio.

If you know him well, that'due south almost incommunicable, Rossi answered.

He is humble but confident, a disciplined dominion-breaker. He is quiet but freely speaks his listen. He is deeply spiritual, only crafty -- a cross between a desert saint and a shrewd politico. He is a human being of ability and action, who spends a slap-up deal of time in prayer and contemplation.

Information technology's a description that many Jesuits might recognize in themselves.

"Contradiction is role of who we are," Rossi said.

But those contradictions often dislocated Catholics in Argentine republic, who pegged him every bit a retrograde conservative. Rossi called the conclusion to transport Bergoglio to Cordoba "humanly unjust" and says information technology caused consternation amongst younger Jesuits.

But Cordoba changed Bergoglio for the better, Rossi said.

"I would say that many things that he is living through today got their showtime hither in Cordoba."

Information technology was similar a seed planted in the hard soil of winter, Rossi said. For many months, the earth looks barren, only in the bound, information technology bears fruit.

"They are hidden from the outside," Rossi connected, "but one is pleasantly surprised to run into where these great people have gone in these moments of silence."

I asked: What was dissimilar about Bergoglio later on Cordoba?

"It is non a different Bergoglio," Rossi corrected me. "It is a fully blossomed Bergoglio, 1 who has amplified his reach and found his mission."

Two years into his exile, in June 1992, Bergoglio was named auxiliary bishop in Buenos Aires. He had grown close to the urban center's Archbishop Antonio Quarracino, who personally petitioned Pope John Paul 2 on his protégé's behalf.

Half dozen years later on, in 1998, Bergoglio himself was appointed Archbishop of Buenos Aires, the most powerful Catholic in Argentine republic.

It was a dramatic reversal from the solitude and suffering he endured in Cordoba, simply Bergoglio said he carried important lessons dorsum home.

"You must live your exile," he told a politician who was forced to resign. "And when you come back y'all will be more merciful, kinder, and y'all will desire to serve your people ameliorate."

Equally Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Bergoglio said, he made sure not to repeat his mistakes. He consulted his assistant bishops and priests, inviting their opinions before making decisions, an approach he has carried into the papacy.

Before I left the Jesuit Residencia, I took one more look at the room where Bergoglio stayed, touching the desk-bound and opening the armoire, imagining it total of a futurity pope's black cassocks.

I walked the short distance to the domestic chapel where Bergoglio had prayed in the night. I knelt in the showtime pew -- his spot -- the hard wood creaking under the weight of my knees. In the early morning silence, with statues of Jesuit saints staring downwardly at me, I took a moment to meditate on everything I'd learned in Cordoba. So I rose and left the church.

The Iglesia de la La Compania in the Manzana Jesuitica or Jesuit Block.

I flew dwelling house with a full notebook, a reporter'southward dream. But I still had many questions, and little time left to find answers -- an editor'southward nightmare.

Looking for the last pieces of the puzzle, I went to see the Rev. Timothy Kesicki, president of the Jesuit Conference in Washington.

Kesicki is a kinetic mix of energy and ideas; a apprehensive homo despite his high-powered position, which essentially makes him the chief liaison between North American Jesuits and the superior full general in Rome. Nicknamed the "black pope" because he wears black vestments and leads the church's largest clerical order, the superior general has unrivaled influence over the Guild of Jesus.

As we talked in Kesicki's downtown Washington office on a contempo afternoon, he would leap from his seat to grab a volume that explained an important point about the Jesuits. Shortly earlier nosotros met, he had sent me a copy of the guidelines for Jesuit provincials, to assist me empathize the decisions that Bergoglio fabricated every bit a Jesuit leader and the decisions Jesuit leaders made about him.

Equally I read a department near "uniting hearts and minds," my optics grew wide. The Jesuit Constitutions, on which the guidelines are based, states:

"Anyone seen to exist a cause of division among those who live together, estranging them either among themselves or from their head, ought with great diligence to exist separated from that community, as a pestilence which can infect it seriously if a remedy is not chop-chop applied."

So, that'south why Bergoglio was removed, I thought. Even if he did nil wrong, he was conspicuously causing a segmentation inside the Argentine Jesuits.

It's non easy to motility men, Kesicki said. Simply ask any secular CEO about the hardest part of their chore: They'll almost always say personnel.

At the same time, Jesuits are called to be in the social trenches, the crossroads of ideologies, places where the Word and the world converge and conflict. Arguments over how to define success in such places seem near inevitable.

"Ane could contend that if yous're non having those kinds of disagreements," Kesicki said, "you're not truly Jesuits."

"So that tension is function of the Jesuits' Dna?" I asked.

"It'south the Dna of the Gospel!" he answered. "Look at the apostles: Peter died upside down on the cantankerous. Is that what he signed up for?"

Earlier in our interview, Kesicki asked something similar: "Was the crucifix a promotion?"

The question rang in my head for a few days. I thought near Bergoglio in Cordoba and the Jesuit spiritual exercises that urge him to identify with the crucified Christ.

I remembered reading an interview with Bergoglio in which he expressed admiration for a volume called "A Theology of Failure," written in 1978 by the Rev. John Navone, an Italian-American Jesuit.

Navone suggests that, in human terms, Jesus was a failure.

He was hated past the Romans and by many of his own Jewish people. Even Jesus' family unit and followers didn't fully sympathise him. About poignantly, Jesus died believing he had been forsaken by God and had failed at his divinely appointed mission.

But that's not the finish of the story. The instrument of decease and despair -- the cross -- becomes a symbol of resurrection, new life, proudly placed atop countless churches.

In 2010, Bergoglio told 2 journalists that Navone's book led him to ponder the theme of patience.

"There are times when our lives practise non call so much for doing as for our 'enduring,'" he said, "for bearing upwardly with our ain limitations every bit well equally those of others."

I called Navone to ask about his influence on the Pope's thoughts: how the indelible Bergoglio had get forbearing Francis.

I asked him how much he knew about Bergoglio'south exile.

Navone knew all about Cordoba.

"At that place was a blest juncture between my theology and his crisis," he said. "It was a kind of light in the darkness to him."

As it happened, Navone and I spoke on the day Francis fabricated it easier for Catholics to annul their marriages, and about a week after he encouraged priests to forgive women who have had abortions.

Navone and I talked about mercy, and how it'due south difficult to forgive others if yous aren't intimately acquainted with your own failures. We talked almost a Pope who travels to the peripheries because he himself was sent at that place. And we talked well-nigh Francis' apparent internal freedom, his refusal to resign himself to others' expectations.

By his ain admission, Bergoglio wasn't a perfect person when he left Cordoba. He didn't fully reconcile with the Jesuits until after he was elected pope in 2013.

But the manner he prays, thinks and acts were all formed by the Society of Jesus -- and, similar all Jesuits, he believes that being good requires more than than avoiding conflict and putting a few coins in the collection plate. Faith is a daily bailiwick, requiring spiritual exercises for the soul, fifty-fifty when -- or especially when -- your soul is suffering, 500 miles from home, alone in a little red room.

I don't know exactly what happened to Bergoglio during his dark dark in Cordoba. I likely never will.

Merely when I encounter the Pope at present in St. Peter's, preaching mercy to all manner of sinners, I can't assist but think dorsum to the former outcast, kneeling in the night of the domestic chapel, alone with the God of surprises.

Source: https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2015/09/specials/pope-dark-night-of-the-soul/

0 Response to "Bergoglio Crucifies Jesus All Over Again"

Postar um comentário